Part of the problem the funeral industry caused for itself many years ago was to embrace the role of a quasi-public utility, a sort of offshoot of the public health infrastructure.

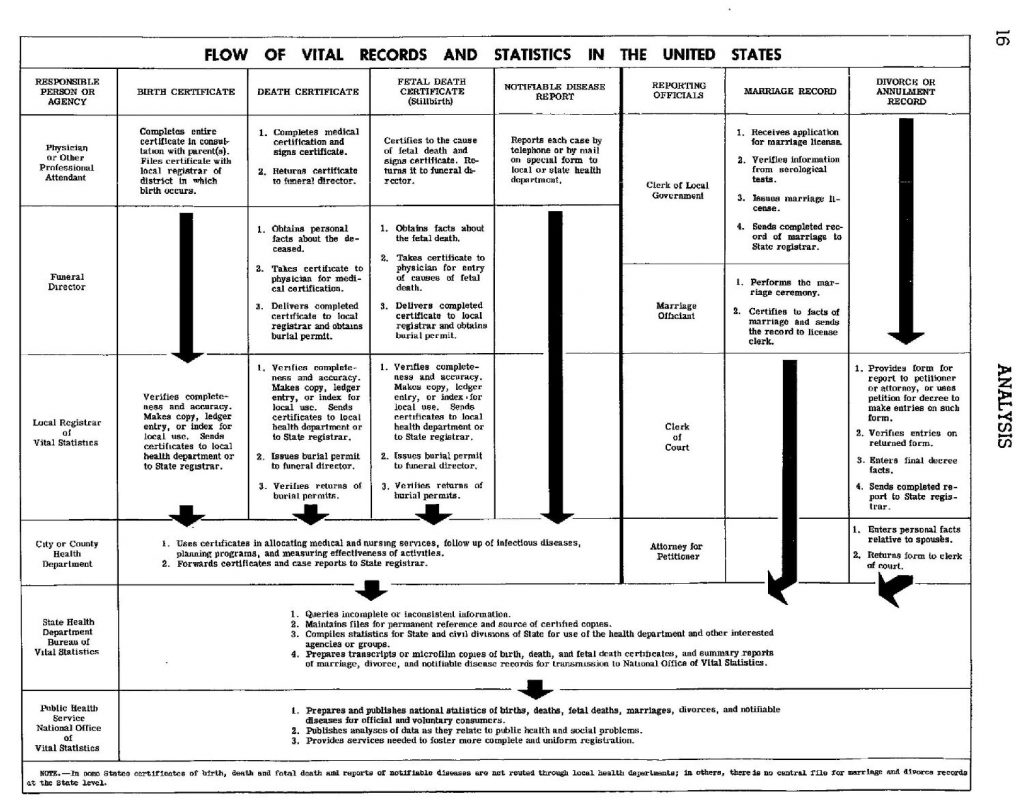

They were justified in doing so. For one thing, it was written into laws and regulations that a funeral director would be involved any time someone died. When the U.S. Public Health Service spelled out the procedure for gathering mortality statistics, as shown in the 1950 Vital Statistics of the U.S. report, there was the funeral director in the flowchart on page 16, right after the doctors and right before the government registrars and health departments.1

Funeral businesses had to be available to make “removals” whenever someone died, under just about any circumstances, making them a 24/7/365 operation. The typical funeral director did not get a lot of holidays off, nor expect a full night’s sleep. Embalming works best the sooner it can be done after death, so the funeral director on call overnight often had a lot more to do than pick up a body after the phone rang.

Although the custom was informal for decades, indigent care also became a somewhat standard part of the business model.

Continue reading A Funeral Industry Trapped By Protective Walls