Part of the problem the funeral industry caused for itself many years ago was to embrace the role of a quasi-public utility, a sort of offshoot of the public health infrastructure.

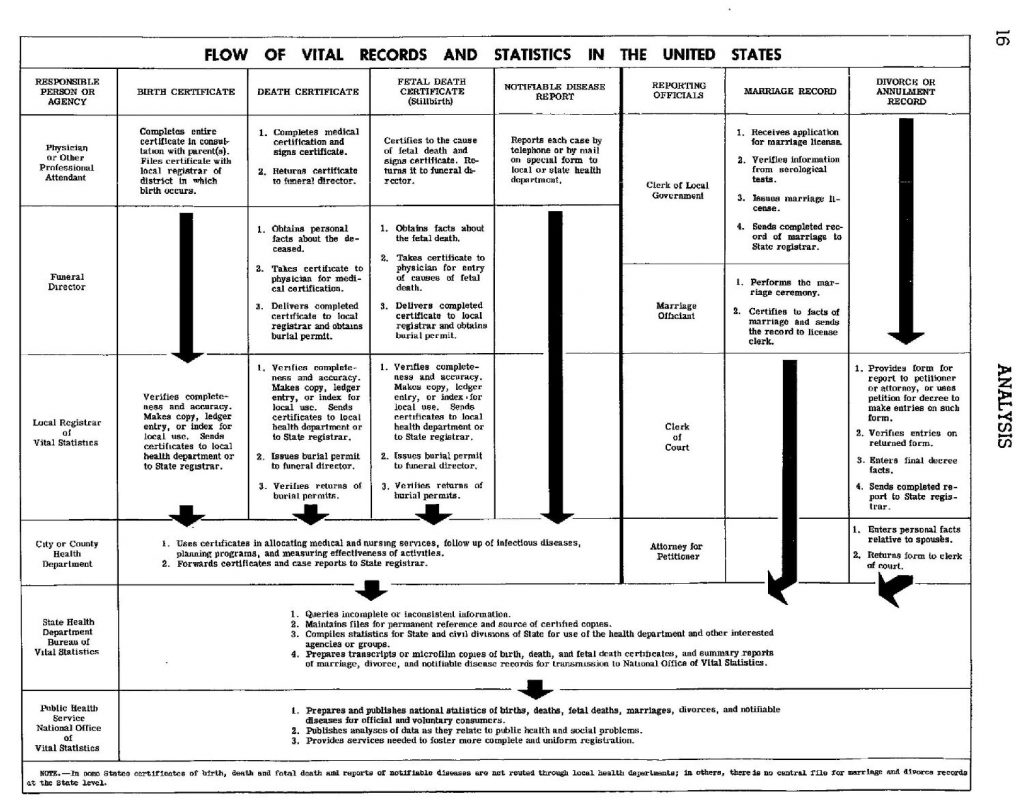

They were justified in doing so. For one thing, it was written into laws and regulations that a funeral director would be involved any time someone died. When the U.S. Public Health Service spelled out the procedure for gathering mortality statistics, as shown in the 1950 Vital Statistics of the U.S. report, there was the funeral director in the flowchart on page 16, right after the doctors and right before the government registrars and health departments.1

Funeral businesses had to be available to make “removals” whenever someone died, under just about any circumstances, making them a 24/7/365 operation. The typical funeral director did not get a lot of holidays off, nor expect a full night’s sleep. Embalming works best the sooner it can be done after death, so the funeral director on call overnight often had a lot more to do than pick up a body after the phone rang.

Although the custom was informal for decades, indigent care also became a somewhat standard part of the business model.

The poorest of the poor were often taken care of by the local government in some manner—either providing a subsidy for simple burial, or cremating the body. But funeral directors often took on cases where the buyers could not pay for a full-fledged funeral, and provided something respectable enough that the family could feel all was taken care of appropriately.

Funeral home owners sometimes provided 100 percent “charity funerals” and did not charge anything, but usually—or probably, because this was not written into any guidelines but is what I’ve gathered from talking to people and reading between the lines—allowed a discounted price, perhaps at or below their cost for the products and services, and sometimes allowed customers to “pay off” a bill that may or may not have been likely to be collected in full. It has tended to be the lower classes who care the most about funeral appearances, so this provision by funeral directors was an important and often unacknowledged public service.

The funeral home facility needed to be kept up and kept open at all times, and serve all who walked through the front door, just like a hospital, but as industry members frequently pointed out, the funeral home was not subsidized like a hospital.2

We should not be surprised, therefore, that the American funeral home owners’ and employees’ basic orientation was sometimes different than that of people in other businesses selling expensive products. There was the presumption of certain flexibility with regard to setting prices. If you ended up giving away caskets and man-hours some of the time, you’d want to take the opportunities to charge absolute full price other times. If you didn’t do that, you’d go out of business.

Any gray area in pricing leads to suspicions. If one family received a certain package of items at a very low price, the next family might pay a much higher price for the same items. I’m not saying it ever actually occurred, but the situation created was an awful lot like one where the price might be based on what the particular customer was perceived as being able to pay. That hypothetical situation is one that does not earn the seller a lot of sympathy from consumer advocates or government bodies.

During the decades of widespread funeral skepticism that kicked off in the late 1950s, funeral directors received very little credit for beneficence to the community, and quite a lot of lambasting for purportedly unreasonable pricing practices. From a long-term perspective, lenience on pricing did not work out so well for the industry, because attempts to compensate for lax procedures in one area with more rigorous procedures in another gave the impression of underhandedness.

In a related process that was understandable but in retrospect may have been a bad idea, the funeral industry has not shirked from opportunities to make government mandate authority work for them. Let’s be fair: if you have a business, and there is a chance the government might make your products and services mandatory, you probably wouldn’t dissuade the authorities from doing so.

If you were working all hours, missing birthdays and vacations, and being available to take on difficult tasks and fill out official paperwork while establishing the chain of custody over human remains, you might even feel justified in welcoming a law that says when someone dies, your company or a company like yours must be called. You might also welcome regulations that say nobody can come in and compete with you by selling ancillary products, such as caskets, if they are not running a full-service funeral home.

Like doctors, funeral directors have to be there when someone dies, so funeral business owners might have welcomed any favorable treatment under law just as medical businesses received.

Fast-forwarding to today, many states’ laws and regulations compel all companies selling funeral-related products or services to maintain the infrastructure and personnel to provide most of these elements. For example, in states like my place of residence, the commonwealth of Virginia, even if you want to sell only cremations to the public, you have to maintain an embalming facility and have a licensed embalmer on staff. It’s an odd rule because most people who choose cremation very likely do not want the body embalmed, but the regulation serves to protect existing businesses from competition and ensure that prices for cremation will remain higher than if someone were allowed to operate a standalone crematory.

Most if not all of such laws were won as a result of funeral industry lobbying efforts, and have served to raise the bar for entry into the market. That’s all well and good for the funeral industry.

Obviously, the protectionist regulations are not so great for consumers because they force people in Virginia, for instance, to pay a lot more for cremation than in states like Florida where standalone crematories are permitted to sell to the public—where people buying cremation are not in effect forced to pay a surcharge for upkeep of an embalming facility.

There are actually three major downsides to the funeral industry’s embrace of protectionism, which as I said is understandable, although like the perceived pricing flexibility which was rooted in charity will probably come back to bite them.

First, protectionism keeps prices higher than they would likely be if the market were easier to enter. High prices annoy consumers, a lot, especially when they can compare prices across markets, which they can. If the history of business and consumer behavior has taught us anything, it’s that people will trample overpriced options to get to lower-priced ones like millions of hot knives through butter. And if you don’t believe that, there is a very long river in Brazil I’d like to sell you.

Second, becoming a quasi-public utility is not putting oneself on the right side of history, at least in American culture. Yes, some of us may like our doctors and our hospitals, but unfortunately the link between funeral homes and public health no longer exists; in fact, that cow probably left the barn a century ago. Today, if you want to become a public utility you are aligning yourself with the electric company and the water company whom, we can agree, don’t have a fan base. Today, the enthusiasm goes in exactly the opposite direction, because going off the grid, cutting the cord, is more the modern sentiment than people saying they love their electric company or cable provider.

Third, while the legal requirement to maintain a certain level of business infrastructure in some states has helped to quash would-be competitors to the funeral homes, it might have created a false sense of security to solidify funeral home owners’ commitment to that high-priced infrastructure model. If the law were to change to allow more consumer-friendly options, those funeral homes might be at a big disadvantage.

As a very smart funeral industry leader, Bob Boetticher, Jr., then-president of the Cremation Association of North America, observed a few years ago:

Many blame the rise in the cremation rate for revenue and profit loss, but it’s not the cremation rate causing this alone. There is increased competition from nontraditional sources that have implemented business models that are not tied to the high fixed costs of a traditional funeral home, and community caregivers who are influencing decisions of consumers due to the fact we haven’t been overly transparent.3

Virginia customers and those in many other states still do not have “nontraditional sources” to choose from. But do laws ever change as a result of consumer demand? Yes, they do, all the time, and they can change very quickly. Legislatures are funny that way. If a movement were to occur requesting more options at the time of death, the government-mandated infrastructure that has protected funeral businesses for so many years may become a millstone around some companies’ necks. The funeral industry’s lobbying agenda may turn out to have been a petard for its own hoisting.

People may decide that the conventional American funeral has been a system imposed, not the result of upswelling cultural beliefs nor customer demand.

-

National Office of Vital Statistics, “Vital Statistics of the United States, 1950: Vol. I, Analysis and Summary Tables” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Public Health Service, 1954), 16, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsus/vsus_1950_1.pdf↩

-

C. Stewart Hausmann, “Who Are We – What Are We – Why We Do What We Do,” in Acute Grief and the Funeral, ed. Vanderlyn R. Pine et al. (Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas, 1976), 170↩

-

Patti Martin Bartsche, “Keeping up with the CANA President,” American Cemetery & Cremation 87, no. 1 (January 2015): 6↩